Blog

Pursuing the Perfect Pressing

The Process of Creating 180 Gram Vinyl Reissues

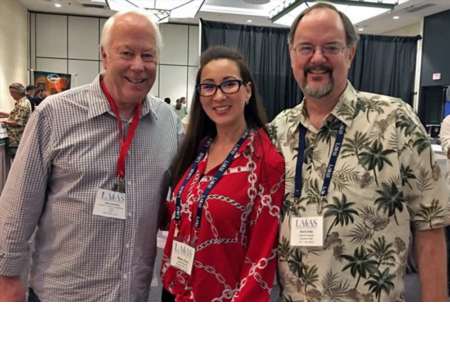

For vinyl lovers, we take for granted the experience of bringing home a new treasure, peeling off the saran wrap and carefully pulling out that awesome new 180 gram version of one’s favorite record. But few of us know what goes into the making of those ultra-high quality releases. Today, we sit down with Abey Fonn, Head of Impex Records, whose boutique specialty label has produced a number of titles that have won awards and the highest possible recommendations from every significant magazine and webzine on the planet over the past decade. Abey is that rare individual whose attention to detail and consistent delivery of perfection has quietly made her a legend in the reissue business and a person with whom we share common values when it comes to getting every detail right. In record making, mastering and production are where the magic lies, follow along as we take you on a guided tour of the modern reissue process.

For vinyl lovers, we take for granted the experience of bringing home a new treasure, peeling off the saran wrap and carefully pulling out that awesome new 180 gram version of one’s favorite record. But few of us know what goes into the making of those ultra-high quality releases. Today, we sit down with Abey Fonn, Head of Impex Records, whose boutique specialty label has produced a number of titles that have won awards and the highest possible recommendations from every significant magazine and webzine on the planet over the past decade. Abey is that rare individual whose attention to detail and consistent delivery of perfection has quietly made her a legend in the reissue business and a person with whom we share common values when it comes to getting every detail right. In record making, mastering and production are where the magic lies, follow along as we take you on a guided tour of the modern reissue process.

JH Abey, let’s start with the basics; walk us through the process and tell us what equipment—in broad brushstrokes (many tools of the mastering trade are considered trade secrets) you work with, who do you retain to do your mastering and walk us through in detail the process Impex uses to produce these amazing gems.

AF First, we generally only use original analogue master tapes when creating a vinyl reissue-I say generally because occasionally the original master is not available. In those instances, we use 1:1 flat (meaning the original pure thing, not a re-mastered or EQ’d version) safety duplicates of the original analogue master. For CD masters, we would also use the analog master if available. And we sometimes use digital masters for CD mastering of newer material, as the quality of modern digital masters is often to a very high standard. For earlier digital material, we will go back and acquire the original analogue master tape and create our own high quality digital 1:1 duplicate master that we then work from.

We use 30 inch per second Studer ½” analogue tape machines, these are simply the finest professional machines ever created and are dead reliable, incredibly important when we’re handling a piece of musical history.

JH For those of us who have heard the term “mastering” used over the years, what is it exactly?

AF Mastering is the process of creating a new document, a record of a specific musical event that has historical significance. From this master, we create a master lacquer which looks like a record but is very soft, then a mother, then stampers which take us into production. In doing this, we work extremely hard to be faithful to the original record, but because we are applying state of the art techniques and materials we can frequently exceed the dynamic limitations of cheap vinyl from, say, the ‘50’s, ‘60’s and ‘70’s and we can also produce much quieter background noise levels. It’s a little like ultra high quality automotive restoration shops that turn out vehicles that are precisely faithful to the original, but run, turn and stop better than the mass production vehicle because the attention to assembly detail is fanatical.

JH Where do you start? I would imagine you have to first acquire the legal rights to these recordings.

AB Yes, exactly, but we only obtain the rights for, say, a vinyl release of a certain maximum number before the rights lapse back to the original studio; Sony or whoever owns the rights. Once we secure the rights, we purchase copies of every quality version of the record possible, although we frequently know, for example, that a certain record was best released in the UK version and that the US or German version was seen as deficient in some regard. Once we have our target fixed by listening to various versions, we take lots of notes of what we hear in levels, equalization and any special techniques used in the original so we ensure that those signatures carry through into our release. My goal has always been to be as faithful to the original recording and not improvise.

JH One of the things that came through loud and clear in my conversations with you leading up to this is that mastering is an interpretive process, not simply a duplicative process. Explain please.

AB Anytime you are making art, it is a creative process. Audiophiles don’t always understand this difference. When I listen as an audiophile, I am working to make sure my system is as faithful to the recording as possible. But when one is in the studio, we are making the recording we are active participants. Say we run our levels just ½-1 db higher than the original, almost no one will know, but it will sound richer and fuller. While we might have nice things said about our release, it’s a distortion of the truth. So we watch carefully all these things to ensure that you get the best possible version of something that occurred 50 years ago.

JH Can we dig into this? Whom do you work with and why?

AF We use the very best mastering engineers; Bernie Grundman is a legendary mastering engineer with literally hundreds of award winning albums and gold records under his belt, and Chris Bellman also legendary in his own right shares Grammy awards with artists like Tom Petty and Frank Zappa and works with artists such as Elton John and Neil Young. Both Bernie and Chris work in both tube and solid state. We also work with Kevin Gray whose work is meticulous. He is credited with more than a hundred top ten and Grammy award winning records. Kevin’s studio features state of the art solid state equipment.

JH So, explain this technique thing. Aren’t they just putting on a tape and playing it into, what, a mastering lathe or something (chuckles)?

AF The mastering engineer uses equalization and levels to adjust and maximize the quality and amount of music that can be put into the mastering lacquer. The closest I can come to explaining it is they use EQ like a painter uses a palette to obtain just the right shadings and tonal colors to get it right.

You have to understand that often these master tapes are very fragile and were made on different brands of tape, some of which don’t even exist anymore. The original engineering notes are often not available to us so it comes down to their decades of experience listening and making masters to push as much music onto the lacquer that that specific piece of lacquer can handle on that day. Much of the time, we have to bake the original master tape for 12 hours at very low temperature to ensure the tape is dry, clean and safe to run over tape heads without destroying it.

JH So how do you make a test lacquer?

AF The test lacquer is a thin soft piece of lacquer that looks like a thicker black record, but it is soft to allow the cutting lathe to create the grooves. We will make a number of these as we try different techniques to get it as close to the original as possible but with greater dynamic range. Each lacquer can only withstand between 8 and 10 plays before it gets too noisy to use. It is cut on a mastering lathe that is a combination of a high quality turntable and a machine tool with a cutting bit that looks sort of like a really sharp razor blade, but much stronger. We have to produce several version of the lacquer before we’re satisfied that each song and side is properly represented.

JH OK, so now you have a lacquer, what’s next?

AF Well, the test lacquer is just a tool we use to check our work, but we can’t press records from this. First we need to produce a master lacquer which is a perfect and much thicker version of the test lacquer that runs around 1/3” thick.

JH And then we can press records?

AF (Laughs) Not yet, we first need to produce an inverse tool. To get grooves pressed in a record we first need to make a version that inverts grooves and what we call “lands” –which are the spaces between the vinyl grooves. This positive master is called a Mother. The Mother is made of metal because it needs to be super strong to pull the stampers off of it without deforming. The production language that I use is that the Mother needs to be a “healthy, clean Mother” (meaning no tiny particles of metal or dirt left in the grooves). To make sure it’s clean we look closely using microscopes mounted at an angle just above the surface and scan every millimeter of groove from beginning to end. If the Mother is clean, we can generally pull about 6-8 stampers from her, these are the actual stamping faces that are used to press records.

JH Take us through the production pressing of your records please, as long as we’ve come this far.

AF We use what I consider one of the finest pressing plants in the world which has been around for decades and is right here in California not far from where I live. RTI has been doing this for many years and we see them as true partners in the process. Rick Hashimoto, the plant manager and his team are incredible in every phase of what they do. There are a few others that also do quality work but RTI’s simply the best. They only use pure nickel for their stamping faces and they plate the lacquers using low temperature pre-plate tanks for at least 12 hours which makes for really quiet surfaces and more records possible from each stamper.

JH OK, so we’re now at RTI and we have between 1-2 stampers ready to go. What’s next?

AF The pressing of records is an art form itself, I’ll have to get you down for a factory tour soon so you can see how it’s done. We use only Thai-sourced vinyl, it’s truly the most consistent from batch-to-batch. We have several different vinyl choices we use depending on the project—I can’t really say any more than that because we’re getting into a sensitive area for me. But Thailand has one plant that makes incredibly high quality vinyl and the best reissue companies all use Thai vinyl pellets.

From raw pellet form, the vinyl is first turned into “biscuits” which are fed into the press. Once the biscuit hits the bottom surface of a heated stamper the top stamper squeezes down on the bottom stamper. It’s very fast taking just 30-35 seconds to turn a biscuit into a vinyl record. We let each record cool in specially-designed racks for 12-18 hours before they are handled. It’s really important to let the record rest and get truly cool all the way through or you’ll end up with warps. Back in the 60’s and ‘70’s they went into a jacket still warm from the press and often were boxed and in a truck rolling toward a distribution center within a few hours.

JH So, at this point we have a perfectly pressed record, we’re almost done?

AF Almost, from there, they are hand loaded into sleeves; we use premium vinyl-lined paper sleeves for most projects. They need to treat the record really well or we just wasted all that effort. We generally use RTI premium HDPE (high density polyethylene) thick soft anti-static sleeves because they use treat the record so gently and leave absolutely no residue. For our very special projects we use very expensive Japanese rice paper sleeves with soft vinyl liners. We’re really proud of our jackets (the outer cardboard cover that contains the artwork and album credits). We exclusively use Stoughton to press our jackets. The Impex team takes special care to obtain really perfect examples of the original artwork and do multiple press checks to get the colors rich and vibrant. Stoughton Printing is a very old company who have won too many awards to list them all but part of their secret is they use a genuine Heidelberg German-made press. This press is affectionately called the Monster and I am told there are only a couple still running here in the US. It takes up a huge building and the floor had to be specially reinforced to withstand the vibration and weight. It’s a very specialized company but we love how our record jackets turn out.

JH Thank you Abey for giving us so much of your time and giving us such a detailed insight into the process used to make these incredible reissues. It’s clear that remarkable attention to detail in every phase of this is the true secret to Impex’s success.